This Includes

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Life

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Crafting Religion

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Governance

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Relationships

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Sexuality

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Crafting Religion

______________________

A playbook for sculpting cultures that overcome demographic collapse & facilitate long-term human flourishing

By Simone & Malcolm Collins

Copyright © 2022

Omniscion Press

Simone & Malcolm Collins

All rights reserved.

Special Thanks to Our Most Impactful Editors:

Lillian Tara

Ben Hoffman

Table of Contents

Culture as an Evolutionary Tool 4

What Motivated Us to Craft a Novel Culture for Our Kids 11

Why is Cultural Diversity Important? 43

Building The Index: A Cultural Reactor 46

The Fundamentals of Culture Crafting 49

Characteristics of Hard Cultures 57

Characteristics of Soft Cultures 62

Characteristics of Super-Soft Culture 64

Characteristics of Pop Cultures 72

Examples of Evanescent Youth Cultures 75

Characteristics of Evanescent Youth Cultures 76

Characteristics of Haven Cultures 77

Examples of Stable Cultures 78

Characteristics of Stable Cultures 79

Arbitrary Self Denial & Fasting: Hard vs. Soft and Pop Cultures 86

Characteristics of the Supervirus 91

What Makes the Supervirus Dangerous? 101

How to Overcome the Supervirus 108

Ancestor & Descendant Worship 118

Catholic vs. Protestant Standards of Evidence 127

The Unique Jewish Standard of Evidence 134

How We Understand Truth: Criteria of Authenticity 143

Relativism & Justice-Motivated Belief Systems 153

Abrahamic Justicle Cultivars 155

The Metaphysical Frameworks of Justicles 165

The Origins of the Supervirus 168

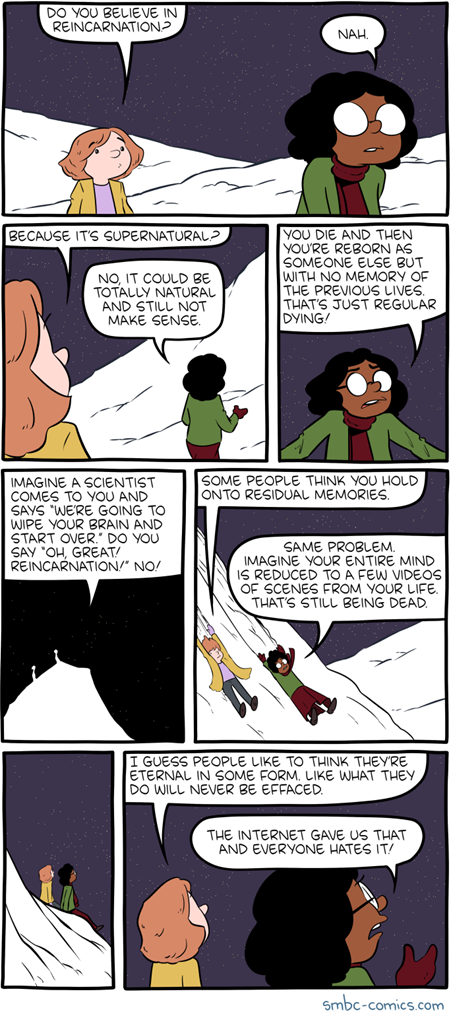

Permanence, Identity, and Creative Destruction 198

Castes & Which Lives Matter 217

Theology: Beginnings, Ends, and Metaphysics 234

End Times & Christian Cultures 251

The Cosmic Consciousness Illusion 254

A Call for Non-Obvious Designations 273

An Example of Non-Obvious Good and Evil 275

Starting and Managing a House 286

Mechanisms of Cultural Memory 295

The Draw of the Sorting Hat 300

“If Only We Could Recapture a Feeling of Community” 301

Teaching Fundamental Social Skills 302

Treating Underlying Causes of Loneliness 304

Secret Societies: Rediscovering a Cultural Technology 308

How Cultures Deal with Aging 315

Retaining Teens Through Rebellion 315

Puberty: Gendered Mental Susceptibilities 326

Post-Death Family Engagement 346

Cultural Approaches to Sexuality 375

J. D. Unwin & Sexual Liberation 384

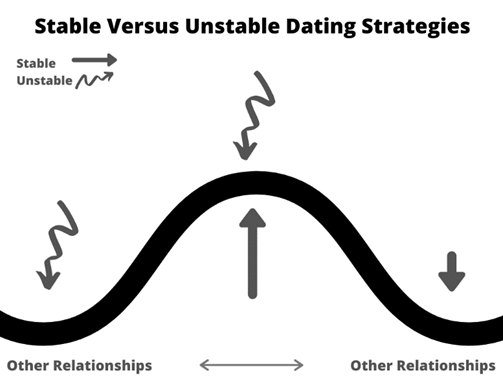

Dating and Partner Finding 386

A Better Solution: The Season 400

Who to Marry and Contextualization of Marriage 406

Dating for a Corporate Family 409

Glorification of Motherhood 424

Genetic Traditions & The Future 432

Hard Culture Opposition to Polygenic Risk Score Screening 445

Institutional Families (Post-Artificial-Womb Family Units) 449

Ecological Niches and Convergent Evolution 456

Roles in Multicultural Ecosystems 460

The Mystery of Modern Jewish Urban Specialization 469

The Myth of a Large, Genetic Jewish IQ Advantage 485

Gun Ownership and Responsibility of Protection 504

Urban vs Rural Approaches to Charity 514

Pets & Domesticated Animals 522

Dogs, Our Evolutionary Partners 528

Emotion and Mental Landscape 531

Victimhood, Politicking, and Industry 532

A Case Study in Cultural Genotypes vs Phenotypes: American vs. Israeli Haredim 543

Relation to Pleasure and the Arts 554

Accidental Cults: MLMs & Life Coaches 568

Accidental Cults: The Mental Health Industry 572

How Culture Relates to Society 589

Immigration and Conservative Values 592

Psychedelics & Hallucinogens 598

What AIs Like to Do for Fun 644

The Logically Aligned Paperclip Maximizer 652

Why are Birth Rates Falling? 671

Decreased Utility from Children 671

Optimization for Happiness & Memetic Shifts 672

Broken Relationship Markets 675

The Capitalism Thesis for Birth Rate Decline 677

Detroit as a Model for Collapse 678

Is an Idiocracy-Style Future Possible? 681

Only Privileged People Can Have Kids! 695

Pronatalism is About Removing Our Reproductive Rights! 697

Forcing a Way of Life on Your Kids is Unethical! 701

Think of the Suffering! (Antinatalism & Negative Utilitarianism) 703

Calvinist Stereotypes in Media 721

On Houses Founded by Sovereign, Childless Individuals 723

K vs. r Selection in Cultivars’ Birth Rates 724

Tragedy as a Source of Opportunity 727

The Immortality of a Vision 729

Cultural Conceptions of Time 733

Stage 1: 0-13 (Up to Adolescence): 740

Stage 2: 14-18 (Up to Legal Adulthood) 741

Stage 3: 19-30 (Young Adulthood) 745

Stage 4: 30-50 (Adulthood) 747

Stage Transition Celebrations 752

Approaches to Play and Authority in Childhood 755

Approaches to Sexuality and Death in Childhood 759

Approaches to Creating Interesting Adults 760

An Honor Code Sample: House Collins’ Honor Code 775

But Surely the Problem will Fix Itself: Behavioral Sinks 786

Alternate History Jews: Samaritans 792

Hofstede’s Other Cultural Dimensions 804

Long-Term vs Short-Term Orientation 812

This book is dedicated to “radiant beings who shall succeed us on the earth.” As Winwood Reade wrote in 1872:

“You blessed ones who shall inherit that future age of which we can only dream; you pure and radiant beings who shall succeed us on the earth; when you turn back your eyes on us poor savages, grubbing in the ground for our daily bread, eating flesh and blood, dwelling in vile bodies which degrade us every day to a level with the beasts, tortured by pains, and by animal propensities, buried in gloomy superstitions, ignorant of Nature which yet holds us in her bonds; when you read of us in books, when you think of what we are, and compare us with yourselves, remember that it is to us you owe the foundation of your happiness and grandeur, to us who now in our libraries and laboratories and star-towers and dissecting-rooms and work-shops are preparing the materials of the human growth. And as for ourselves, if we are sometimes inclined to regret that our lot is cast in these unhappy days, let us remember how much more fortunate we are than those who lived before us a few centuries ago. The working man enjoys more luxuries to-day than did the King of England in the Anglo-Saxon times; and at his command are intellectual delights, which but a little while ago the most learned in the land could not obtain. All this we owe to the labors of other men. Let us therefore remember them with gratitude; let us follow their glorious example by adding something new to the knowledge of mankind; let us pay to the future the debt which we owe to the past.

All men indeed cannot be poets, inventors, or philanthropists; but all men can join in that gigantic and god-like work, the progress of creation. Whoever improves his own nature improves the universe of which he is a part. He who strives to subdue his evil passions—vile remnants of the old four-footed life—and who cultivates the social affections: he who endeavors to better his condition, and to make his children wiser and happier than himself; whatever may be his motives, he will not have lived in vain.”

Warning

This book will be wildly offensive to most people.

At its core, The Pragmatist’s Guide to Crafting Religion is a meditation on how we can intentionally construct a culture/religion that will be “evolutionarily successful” and spread. Within it, you will find a heavily annotated playbook for constructing a cultural/religious framework optimized to preserve (rather than erase) the individual traditions, values, and worldviews of those who join while maximizing autonomy and individual efficacy. We will be completely transparent as to the motivation behind every decision made in its fabrication.

This book is written from a secular perspective to be relevant and useful to those who want to build a family culture that is intergenerationally durable. That said, the tools and tactics described in the coming pages can be used with equal alacrity to strengthen and reinforce an existing religious framework.

In this book we make generalizations about cultural and religious groups, as it is impossible to write a book on culture and religion without doing so. We also take a strong pronatalist perspective because outside of cases of conquest or conversion, most of the time when a culture “wins” over other cultures, it prevails by producing more kids who remain within that culture. If this is not what you were looking for when buying the book, please email us (at [email protected]) and ask for a refund. Regardless, all proceeds from this series go to the Pragmatist Foundation, a nonprofit which is presently focused on building a better form of secondary school (middle school and high school).

Finally, unlike our other books, The Pragmatist’s Guide to Crafting Religion is intended to be read in order and will explicitly signal when a section or chapter is safe to skip. This book gives readers a choice between three reading experiences: If you want the most compressed experience, skip chapters marked as skippable. For the normal experience, read the book and stop at the Appendix. For the “extended cut,” read the bolded footnotes (which lead to deeper pontification—not sources, definitions, or simple explanations) and skip forward to read each of the Appendix chapters as they are referenced in the book.

As with all our books, we will gladly share a free audiobook copy with you. To request one, visit Pragmatist.Guide/ReligionAudio.

Culture as an Evolutionary Tool

Culture is the means by which complex behaviors—behaviors that cannot be easily encoded into biological instinct—“evolve.” This is what makes cultural memes[1] fundamentally distinct from memes in general: While general memetic sets replicate primarily by using a host to infect other hosts with said meme, cultural and religious memetic sets primarily spread by influencing the fitness of any given host (by fitness, we mean genetic fitness—the number of surviving offspring—not the quality of life of those offspring).[2]

Because culture can affect a person’s number of surviving offspring, traditional evolution (not just memetic evolution) shapes culture. This interplay allows complex behavior patterns to emerge among groups of people well before those behavioral instincts might otherwise biologically evolve (consider that ritual Islamic hand washing evolved long before medical science understood the advantage of this behavior).[3]

A culture can be thought of as ever-evolving software that sits on top of—and synergistically interacts with—both biological hardware and firmware, addressing flaws our biology hasn’t had sufficient evolutionary time to address. To go further with this analogy: Biological evolution provides some basic coding, much like a low-level programming language might for a given hardware, whereas cultural evolution manipulates the high-level, object-oriented code that lets us program highly nuanced behaviors.

We can illustrate this dynamic with a colorful example: In The Pragmatist’s Guide to Sexuality, we explore copious evidence that humans almost certainly evolved to, by default, create polygynous (one man, many women) cultures (though not necessarily relationships).[4] However, above certain population thresholds, monogamous cultures outcompete their polygynous counterparts, likely because monogamy produces measurably lower rates of cheating, rape, murder, terrorism, corruption, and other anti-social behaviors instigated by high rates of unattached males—an inevitable byproduct of polygynous cultures.[5]

While 83%[6] of individual human cultures are polygynous,[7] nearly all of today’s most dominant cultures are monogamous, thanks to the historic competitive edge granted by this practice. By reducing societal ills, such as terrorism and corruption (via lower population percentages of unattached men), cultures practicing monogamy have the upper hand when spreading and conquering neighbors.

Rather than taking the evolutionary time needed for human biological predilections to evolve toward structuring societies monogamously by default, cultures that effectively enforced monogamy quickly outcompeted their rivals. This is what we mean when we say that culture supplements biologically evolved elements of human consciousness by accelerating the evolution of cognitive proclivities beyond the capacity of pure evolutionary pressure on genes.

It fascinates us how quickly people cast out aspects of their traditional cultures without understanding why those elements evolved. Many throw out the “hard stuff” in their cultures, such as fasting and arbitrary self-denial, without understanding those cultural practices evolved both for general health reasons and to strengthen the individual’s inhibitory pathways in their prefrontal cortex. Consider that strengthened inhibitory pathways likely offer some protection against intrusive thoughts and, as a result, lower rates of anxiety and depression.[8]

Almost every common cultural practice exists because it increases the fitness of cultures that practice it. Keep in mind that fitness is morally blind. Sometimes, measures taken to increase fitness are highly immoral. Sometimes, increasing fitness means lowering rates of depression with seemingly arbitrary rules. Other times, maximizing fitness means forcing gay people to pretend to be straight or be killed because socially accepting same-sex couplings has historically lowered birth rates.[9]

This is not one of those books that assumes “natural” or “traditional” things to be better or somehow inherently good. As we demonstrate in The Pragmatist’s Guide to Sexuality, humans almost certainly have a proclivity toward infanticide of stepchildren. The fact that humans have evolved certain cultural or biological instincts doesn’t mean we should encourage those behaviors.

We, nevertheless, choose to inhabit a world of pragmatic truth. The human brain evolved to work within a strict cultural framework. Our brains and cultural/religious mechanisms co-evolved to work together. Operating our brains in a cultural/religious vacuum is like trying to run a machine without any grease—it will start fritzing and fall to pieces at a much faster rate. When individuals cast off their ancestral cultural/religious frameworks or make up new ones out of whole cloth without carefully investigating the instrumental roles cultural practices play, is it any surprise that they find themselves barely holding it together mentally by their mid-30s while desperately searching for community and purpose? Instead of taking the winding road to their destination, they decided to just beeline their car (brain) straight through muddy fields and, in the process, damage their car.

Because it is endlessly annoying to keep referring to both culture and religion, we will call specific cultural-religious memetic packages “cultivars.” We chose this word for its colloquial definition as well as its etymology (cult+variation), with “cult” originally non-judgmentally referring to care, worship, culture, and reverence (it is where our word “cultivate” comes from). Honestly, we’d prefer to call this book The Pragmatist’s Guide to Crafting Cultivars, but as our use of the word is not yet pervasive, “religion” must be our public-facing shorthand for “an intergenerational culture and worldview.”

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Crafting Religion is focused on a fun experiment: Can we craft the perfect cultivar?

This is a selfishly motivated experiment. We want to create a powerful culture for the benefit of our children and the growing tribe of “Pragmatists” who read our books. With the framework we present, you, too, should be able to join us and attempt to create your own lasting culture. It might be a few centuries before we see the results of this experiment, but we genuinely believe that failure could lead to the death of our species and eventually all life (we know, it’s dramatic—more on that shortly).

Exploring cultivar differences and how they affect adherents’ life choices in an effort to develop a culture that ultimately persists through millennia is like studying comparative evolution while spending a good deal of time trying to create the ultimate evolutionarily competitive organism that may also do some benefit to civilization. (Think: An organism that can terraform other planets.)

In short, it’s really fun.

This brings us to what will likely be one of the most unique elements of this book: While other people have written extensively on cultural and memetic evolution, to our knowledge, they almost all have an intensely antagonistic perspective toward religions in general—and especially toward stricter, more “conservative” religions. This deeply clouds their perspective on the wider civilizational game at play.

We hold a deep admiration for the lives led by adherents of many stricter religious traditions, from members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (i.e., Mormons) to Evangelical Protestants and Anabaptists.[10] It may seem odd to encounter people like us—affiliated with the Effective Altruism and transhumanist movements—speak with greater reverence for Amish culture than their own. Still, despite the above cultures’ faults, they are out-competing our own at the evolutionary and civilizational level, not just in terms of birth rate but also in surprising realms like mental health.[11] To dismiss these groups’ competitive advantages requires blinding arrogance.

Throughout history, as humans developed social environments we had not biologically evolved to handle (such as early cities). Through the selective pressures on cultivars, we evolved social technologies that permitted relatively rapid adaptation. Unfortunately, from the internet to megacities, the rate of change humans encounter today has become so rapid and momentous that even social evolution may not have time to act before permanent damage is inflicted. We may have reached a point in human history at which we must intentionally engineer cultural solutions to ensure a prosperous future for our species. To do so, we must understand why cultures evolved the way they did.

What Motivated Us to Craft

a Novel Culture for Our Kids

If a culture has a low birth rate—no matter how good it is at converting people—it will either eventually use up the existing supply of non-adherents or become parasitic, essentially using other cultures as breeding pits of livestock from which it expects to harvest members to keep its Goa’uld-like subculture alive.

We could be just amoral enough to sympathize with this cultural strategy, if not for the fact that the few cultures that still have a high birth rate are seeing that rate fall. Vampires might be sexy and cool when they are in the minority, but we are well past that stage and will soon be entering one in which, bereft of life to suck from the world, vampires will turn on each other.

Birth rates are falling much faster than many dominant societal narratives imply. The global fertility rate for all of Latin America and the Caribbean fell below replacement rate (2.1 babies per woman) in 2021.[12] India will achieve that status in 2022.[13] China is expected to be at half its current population by 2066.[14] First-generation immigrants in the U.S. fell below repopulation rate in 2019.[15] Already 115 countries, representing about half the world’s population, are below replacement rate. By the end of the century, nearly every African country is projected to have a rapidly declining population.[16]

Even strict religious fundamentalism does not protect against this decline. “Between the 1980s and the 2010s Iranian women reduced the rate at which they had children from 6.5 to 2.5, faster than the pace of the one child policy in China.”[17] Consider even that since 2014, Iran has been doing everything it can imagine to restore an above-replacement-rate birth rate to no avail.[18] (Overall, Muslim majority countries are not as resistant to demographic collapse as some would have you believe and are projected to fall below replacement rate on average in the 2030s.)[19]

In 2021, the Mormon population in Utah almost fell below replacement rate.[20] This is not a “canary in the coal mine” moment; we’ve reached the metaphorical point at which miners’ skin is bubbling and sloughing off—all while many claim this dramatic drop is a “minor inconvenience.”

People don’t seem to “get” how quickly this effect will be felt. South Korea has a birth rate of 0.81.[21] For every 100 South Korean great-grandparents, there will be 6.6 great-grandkids (at the 0.7 fertility rate predicted in South Korea by 2024, this amounts to 4.3 great-grandkids.).[22] Imagine if we knew a disease would kill 94% of South Koreans in the next century. We are not far from Korea’s present predicament, as recently as the mid-90s, South Korea had a birth rate close to the present birth rate in the U.S. (1.7 in 2022). (For information on why this is happening, see: “Why Are Birth Rates Falling?” in the Appendix on page 671.)

Many media narratives suggesting demographic collapse is not a big deal point to unexpected spikes in birth rates, distracting from the larger picture. For example, there was a slight uptick in birth rates for one year during the pandemic in the U.S. While conservative press made a big deal about this, the phenomenon was illusory and irrelevant from a statistical perspective.[23]

Across the world we see a similar phenomenon: Countries explode in population as resources expand, then drop off (and begin to collapse) once citizens gain wealth and adopt greater gender equality. While many countries have yet to reach this crescendo, most are well on their way—and we want them to be. Gender-egalitarian societies with low levels of poverty are awesome.

Imagine someone arguing in favor of female disempowerment and poverty for a nation just so we can rely on it for a steady supply of human capital. Horrible!

On a societal level, we must figure out how to have our cake and eat it too. We believe it is possible for a society to maintain a stable population, empower women, and keep poverty low. The catch is that nobody has successfully achieved this.[24] That’s a big deal because our entire economic system—heck, our entire civilization—runs on the assumption of aggregate growth.

The economy = productivity per worker × number of workers

Historically, both productivity per worker and the number of workers have increased. Stocks have consistently increased over time, in aggregate, because these two factors have consistently increased.[25]

We can no longer take these increases for granted. While productivity per person only increases linearly,[26] most of the developed world is about to see populations decrease at exponential rates (this is an inevitability when places like the EU have a fertility rate of 1.5). When this happens, the stock market, on average, will begin to shrink. When that happens, people will stop putting their money there—we will stop investing in the future.[27] The civilization we have built is about to undergo a massive and permanent change. The world in which our grandkids will grow up will not resemble our own.

As our stock in the world has risen, so has our pessimism. We don’t think anyone can stop what is coming. Through our privileged educational backgrounds at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business and Cambridge, we have seen what society’s “best of the best” are doing. This is also in conjunction with our work in venture capital and private equity, Simone’s year-long stint as Managing Director at Dialog (a secret society founded by Peter Thiel with membership limited to the best-in-class players from any given field), and work as consultants helping high-profile organizations like Schmidt Futures build their own invitation-only societies for leaders across the private and public sectors. There is no secret back-up plan among the elites.[28]

We no longer believe that it is possible to avert most of the severe economic, governmental, and social consequences associated with a “hard landing” from population collapse. However, we offer one caveat: Artificial intelligence may act as a literal Deus ex machina. If AI does sweep in to save the day, the nature of society will change dramatically. See our exploration of AI Apocalypticism on page 640 for more detail on possible implications.

Fortunately, humanity’s present quagmire presents opportunity and a path for further consolidation of power by groups that think like us—the new Sea Peoples. Rapidly dropping birth rates among the increasingly sterile and decaying “elite” circles in our society mean anyone who can craft a self-sustaining new cultivar that produces competent, highly educated, technophilic individuals gets the chance to write the future of human civilization.

A population collapse will produce a systems-level collapse of today’s dominant civilization. This means cultivars crafted to survive this period must be able to withstand hard times, though perhaps not the sorts of “hard times” you’re presently envisioning. When presented with the concept of “civilizational collapse,” people often visualize society descending into a Road-Warrior-like dystopia, when in reality, it is rarely very obvious to people on the ground when a civilization collapses, be it Rome, the Mayan civilization, or our own (to an average person in Roman Gaul during the collapse of the Western Empire, the change would have been only lightly perceptible in their daily routines—a certain food becomes impossible to find, certain roads become more dangerous to travel, etc.).

Civilizational collapses appear more like:

- An exodus of the elite from major population centers

- A rapid decline in infrastructure quality in densely populated areas

- A breakdown of supply chains (e.g., some stuff you used to be able to get at grocery stores permanently disappears from the shelves)

- Growing hostility toward ideas that deviate from orthodoxy

Our society relies heavily on one presumed truth: That the wealth of the world will always grow. Cities and countries fob off huge amounts of their payroll to the next generation through unfunded pension programs and debt with the presumption that said generation will have more money than they did. What if the next generation doesn’t? Debt payments and pension spending will assume a larger portion of the money needed to keep things running.

This isn’t exclusively happening at the level of cities. We saddle every level of the economic system, from our land to businesses, states, and nations, with debt. We have essentially leveraged our entire civilization. This provides enormous wealth in times of population growth, but …

Imagine that 50% of a city’s budget goes to pensions, social security-like programs, and debt payments (this was the case in Detroit[29])[30]. This is fine if the population grows by half, as that 50% of the budget becomes 33% and is quite manageable. But what if the tax base shrinks? If the city’s population and tax base shrink by just 30%, its usable money does not decrease by 30% but rather by 60%. If the tax base were to shrink by 40%, the usable portion of the city’s budget would drop to 10%. This is not unrealistic when you consider that in New York City, just the wealthiest 38,700 residents, 0.5% of the city’s population, pay 42.5% of taxes.

Ironically, progressive tax policy, which has led to the elite paying most of the taxes, has turned cities into business units that need to primarily serve the needs of the ultra-elite, or risk losing their primary funding sources and going bankrupt as a result. In a post-COVID world, where remote work is a possibility, the value proposition of cities to the ultra-elite is quickly eroding.

As cities try to operate on smaller portions of their budgets, they will become less attractive places to live, further reducing the proportion of wealthy people who want to live in them (who pay the majority of taxes). As expenditures like police budgets are cut, wealthy people leave cities.[31] As fewer wealthy people opt to live in cities, we’ll see a snowball effect of worsening conditions for those who remain economically trapped in urban areas.

The above scenario is largely what happened in Detroit (with a 60% population drop over the last half-century). While the headwinds that led to the population collapse were different, Detroit presents a sobering case study demonstrating how our existing infrastructure starts to break when a tax base rapidly disappears. (See: “Detroit as a Model for Collapse” in the Appendix on page 678 for more detail.)

Suffice to say when a population starts declining, it does not mean everyone gets to live in bigger, shinier apartments. As population declines, real estate values plummet. Plummeting real estate values drive people to stop investing in building maintenance, causing homes and buildings to rot and fall apart, leading to an endless sea of urban blight.

What about increased lifespan? That should offset things, right? Increased lifespans might help if they were actually increasing. In practice, some developed countries like the USA have actually seen lifespans contract over the last half decade or so.[32] Even when lifespans were growing, they did so linearly (recall that fertility is declining exponentially).

Outside of a dark horse artificial intelligence changing the game, the future described above is inevitable at this point. It is too late to not hit this iceberg. All that is left for us to do is ensure future generations get on a lifeboat. This book aims to give our kids a fighting chance while acting as a signal light to like-minded families.

Humanity’s Genetic Shift

When a person gets severe radiation poisoning, some time passes before they feel the adverse effects. Their DNA has functionally been scrambled; their cells can’t divide; the person is dead—they just don’t know it yet. Many wildly popular cultural movements are currently in this state. It may be easier to coax a caged panda to reproduce than it would be to convince a cosmopolitan progressive to raise their own kid.

Given what large meta-studies like Genetic and Environmental influences on Human Psychological Differences[33] show about the heritability of political ideology,[34] we should expect some shift in how the average person reacts to these sterilizing political memes. (Note: Studies show even specific traits like altruism[35] and prosociality[36] have an approximately 30% to 50% genetic component.)

But surely this change will be slow … right? Actually, it is already measurable. One group of researchers quantitatively demonstrated how differential fertility rates can substantially impact attitudes around social issues.[37] From 2004 to 2018, differential fertility (more conservative people having more kids) increased the number of U.S. adults opposed to same-sex marriage by 17%, from 46.9 million to 54.8 million.

Note: Support for LGBT issues among the youth is rising over time but not as much as it would if birth rates were equal among all cultures. Given the current severe and rising difference in birth rates between families who support these issues and those who do not, we should see a flip, with support steadily decreasing within a generation or two.

Because unmarried and childless people vote more liberally, this change makes a population more liberal within a generation[38] but more conservative between generations.[39]

Our nonprofit, Pronatalist.org, paid Mohammed Ali Alvi, a researcher at Mayo Clinic, to go over data collected by Spencer Greenberg’s organization Clearer Thinking to get a rough picture of the likely sociological and cultural profile of future Americans by searching for common traits among those having more children.

To summarize: Our original hypothesis was wrong. We assumed that only a propensity toward religious extremism would be associated with a high birth rate. While we expected the overall “tone” of humanity would change, we didn’t think there was much to worry about because our own family falls pretty far on the religiously extreme spectrum and we know firsthand that religious extremism can lead to positive outcomes. It should have been obvious to us that hardcore progressives have just as much genetic religious extremism backing their beliefs as the most steadfast Swartzentruber.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the data suggests that we should expect future generations of Americans to hail from cultures that feature genetic correlates associated with being:

- Significantly more tribalistic (hesitant to interact with outsiders, such as different ethnic and religious groups)

- More drawn to strictly hierarchical power structures (fascist leaning)

- More dogmatic

It is not fervency of beliefs that protects a member of a traditional cultivar from the influence of sterilizing memetic packages but their unwillingness to listen to or consider the perspectives of people not within the “in group,” as well as their readiness to dehumanize those individuals. This is called the right-wing authoritarian personality cluster[40] (though it can present on both sides of the political spectrum, it is more a measure of authoritarian inclination)[41] and it is known to have genetic correlates.[42] We are not the only ones to find that this group is outcompeting the religious cluster.[43]

These are the traits for which our current society selects. Political ideologies that thrive on them should be expected to grow. Edgelords were afraid of an “Idiocracy” world in which only people they considered “stupid” had super large families when the data instead suggests we are heading towards an “ISIS-ocracy”. (Note: We don’t mean ISIS to represent Islam. Groups like ISIS exist across religious branches—we just refer to ISIS as a culturally evocative group that fits the above criteria associated with high birth rates.)

If you want to read about the possibility of an “Idiocracy Scenario,” see: “Is an Idiocracy-Style Future Possible?” on page 681 of the Appendix. This scenario can be useful to review if you think the process of human mental traits adapting to evolutionary pressures is slow. However, if you want to run the math yourself, check out Rapid Evolutionary Adaptation in Response to Selection on Quantitative Traits.[44] Suffice to say current rates of IQ change suggest that the human sociological profile should shift around one standard deviation about every 75 years where strong selective pressures exist.

Genocide through Inaction

Is there a moral responsibility to save a culture or ethnic group going extinct due to a low birth rate? Entire cultures and ways of life don’t just quietly disappear because of low birth rates—do they?

People often imagine cultures and ways of life conquering each other through wars, genocide, and violent conquest, but reality is rarely so dramatic. Our family has Calvinist roots (you might be more familiar with the tradition under its sub-branch of Puritans). Historically, Calvinist culture shaped almost every aspect of the modern United States (and, to an extent, the current world order). Calvinists made up two-thirds of Declaration of Independence signers,[45] many of the founding fathers (Simone is actually the closest relative of her generation to George Washington)[46], around a third of prominent abolitionists, and are often credited with the invention of capitalism.[47] Yet today, Calvinists make up less than 0.5% of the U.S. population, and most of those individuals are only theologically Calvinist rather than culturally so.

Calvinist culture went from crafting an entire world order, making up between 55% and 75% of Americans around the time of the revolution,[48] to virtual extinction in a single century without anyone noticing. For reasons we will explore the next chapter, Calvinism secularized[49] about a century earlier than other religious traditions. As such, their birth rates dropped earlier. Essentially, Calvinist culture demonstrates just how quickly your own culture can disappear and how no one will even miss you (kids today read about the Calvinist Puritans and don’t think to ask, “What ever happened to those people?”).

Just as a culture can collapse in a single century, one can rise to dominance in the same time frame. For example, a single family with eight children per generation would have over a billion descendants in just ten generations. Suppose the family is also able to effectively recruit new members, they could achieve the same feat in a quarter of that time. An example of this phenomenon can be seen in the Hutterites, a group of anabaptists related to the Amish that grew from a population of 443 people to over 50,000 in just 140 years with virtually no external conversions. There will be 5.6M Hutterites within the next 140 years at this growth rate.[50]

The crazy thing about all this is that population collapse could be solved by just one family. One family having eight kids for just 11 generations produces more descendants than there are humans on Earth today. Such success, however, would be hollow. A homogenous society, even if it mirrors our personal values, is fragile. Anyone familiar with the Irish potato famine knows the risk accompanying any literal monoculture. We only win if we succeed in stabilizing human population levels and ensuring that the resulting stable state is heterogeneous, saving as many cultures on the edge of extinction as possible. For example, if we do nothing, some of the oldest and most unique human cultures, such as the Parsi and the Jains, will be virtually extinct by the time our great-grandchildren are growing up (not everyone in a culture needs to die for it to collapse, just enough for it to lose its internal network).

We will do what we can to ensure our family achieves the above feat. We furthermore aim to equip you to do the same with yours. Our goal is to create a “cultural reactor” we’ll call the Index: A collection of groups capable of accelerating natural cultural evolution through the incorporation of families with different traditions and perspectives.

The Index is meant to serve as a self-contained cultural ecosystem strong enough to carry the torch of civilization through the encroaching darkness. We invite other Pragmatists to join us in trying to create a unified network of cultures inspired by a variety of backgrounds and life experiences. Together, we can create a network of cultures capable of shouldering the burden of civilization as so many others shrug the burden of procreation.

We wrote The Pragmatist’s Guide to Religion not to create followers but to establish a network of friendly competitors with a shared nervous system.

Defending Pronatalism

If you have one of the following complaints against pronatalism, please consider visiting the corresponding section in the Appendix on page 689. We take arguments against pronatalism seriously and think you may find more nuance to the following issues than one might assume.

- But … the Environment! p690

- Only Privileged People Can Have Kids! p695

- Pronatalism is About Removing Our Reproductive Rights! p697

- Pronatalism is Racist! p698

- Forcing a Way of Life on Your Kids is Unethical! p701

- Think of the Suffering! (Antinatalism & Negative Utilitarianism) p703

Culture vs. Religion

We use the word cultivar when discussing a mix of religion and culture that acts as a distinct memetic package. While in our society, most cultures heavily overlap with religions, the two are not intrinsically bound, making it more accurate for us to use a distinct word.

Contrast the cultivars of Irish and Latin American Catholicism to see how religion can be heavily associated—but not 100% correlated—with culture. Both cultivars ostensibly hail from the same religious background but feature many differences. Having lived among both for a period, we see it is not just a stereotype that drinking is much more important to the Irish than the Latin cultivar. Yet, this difference has no religious underpinning; it’s purely cultural. In fact, in Peru (one of the countries in which we’ve lived), people raise their eyebrows when we order beer with lunch—this is not surprising given that 60% of the population sees drinking alcohol as actively immoral.[51] Contrast this with 84% of Irish adults who drink.[52]

The Addams Family presents a great fictional example of a cultivar with an ambiguous religious underpinning. Unlike their derivatives, such as the Munsters, the Addams Family is not primarily monstrous because they are literally monsters but because they have a unique family culture (in most iterations at least). The family’s cultivar acts as a lens through which they view reality, transforming the way they interpret the world. For example, they might contextualize dying plants or an unplanned financial loss in a positive context. Because of their cultural lens, they may glean positive feelings from these otherwise “negative” stimuli. However, nothing about the family’s cultivar is specific to one religious perspective or another (outside of a few largely throw-away traditions mentioned here or there).

The Addams Family also helps to dispel the myth that there is some sort of universal “non-religious” cultivar. The Addams Family could very well be atheist, but their daily experience of the world would be radically different from that of most other atheist families. If one chooses to raise their kids in a secular household, there are still many choices about family culture to be made. It is not as though there is a single, correct, “logical” lens through which the world can be viewed. Even if a person is atheist, the culture they choose to live by or build for themselves fundamentally shapes how they experience the world.

Finally, it is important to remember that one person doesn’t just adopt one culture. People switch between cultures when in specific social contexts. Micro cultures often exist around specific activities such as sports, drinking, or secret societies—all with their own rituals, traditions, mystical beliefs, and value sets. While these micro-cultures do not matter in a civilizational context (thus, we will usually only focus on “core cultures”), we will touch on them occasionally as new core cultures can sometimes evolve out of them.

Our Cultural Bias

This book is akin to a guide to remodeling a house that uses the remodel of a specific house as a narrative throughline. The decisions made during that remodel are not mandates for you to make the same decisions. The ultimate goal of the book is not to encourage all homeowners to remodel in the same style. Instead, it is to create a coalition of homeowners who have intentionally renovated historic houses for the modern age (put in internet, plumbing, electricity, smart thermostats, and solar panels while cleaning out the termites, stripping lead from the walls, and reinforcing weak parts of the foundation).

In this metaphor, the house we’re remodeling—i.e., the culture we inherited and have chosen to reshape and optimize—is secular Calvinism.[53] Calvinism is a religious sect from which Puritans hail; Calvinist is to Puritan as Anabaptist is to Amish (all Puritans are Calvinist, but not all Calvinists are Puritans).[54]

As our “old house” to be “remodeled” is secular Calvinism, you may find it helpful to understand what the original construction looks like. Understanding our cultural position will help you personally correct for personal biases and distortions created by the lens through which we see the world. (It might also give you insight into the world perspective of a seldom-discussed culture, something we always find interesting.)

Scott Alexander, author of the popular Substack/blog Slate Star Codex, describes the stereotypical Calvinist (specifically Puritan, the better known regional sub-group) as an “Eccentric overeducated hypercompetent contrarian … who takes morality very seriously.” “People complain that there is too much neo-Puritanism around these days,” Alexander wrote, “but they usually just mean people are moralistic reformers. I have the opposite worry: what happened to these people? When was the last time you saw somebody called Hiram invent five different crazy machines, found a new religion, and have twelve children who he named after Greek nymphs? Anyone who is serious about “Making America Great Again” should be deeply worried. … The virtue-obsessed nonconformist eccentric inventor philanthropist – has almost disappeared.” [55]

The one thing almost everyone knows about Calvinists is that they believe in predestination—which we absolutely do. A mechanistic, clockwork understanding of reality is one of the foundations of our culture. The one thing almost everyone gets wrong about Calvinism is that they assume a belief in predestination implies a lack of belief in free will.

Just because past events could have only occurred in one way from our current perspective in the timeline does not mean we lacked free will in the moment. When we look back at the events of yesterday from our perspective today, the day could have only happened one way—and yet every decision we made yesterday was made with our own free will.

While events that will take place in the future seem limitless, they appear fixed when we look back along our timeline. Theological Calvinists believe God exists outside that timeline and therefore, from His perspective, future events are no different from past events. Just as God’s perspective outside the timeline does not negate free will, your perspective today—at this point in the timeline—does not negate free will you exercised in the past.[56]

Secular Calvinists hold a similar belief but see the laws of physics—rather than God—as existing outside the timeline. The fact that physical laws exist outside the timeline and necessitate its path does not negate free will. In other words, just because our lives can only occur in a single way from the perspective of the laws of physics does not mean we lack free will from our own present perspectives. (The same is true if we live in a branching timeline, in which case each individual stream of the timeline is still determined by a mechanistic set of rules over which we have no influence.)[57] This understanding of reality influences how our intentionally designed culture interprets matters like emotional states (something we address later in the book). It also explains why we believe a person’s choices can both shape a timeline and be predestined within it.

Discussion of free will dovetails well into Calvinists’ assumption of the total depravity of man. Culturally, this means we have a very dim view of individual self-worth and the worth of humanity as a whole: Humans are wretched—we must strive to overcome our nature while knowing we are destined to fail. In other words, this viewpoint acknowledges how fallible humans are but, nevertheless, maintains that we should hold ourselves to a higher standard.

While Calvinists are rare these days, they used to be common enough that their stereotype became a media trope. Cultural Calvinism is almost holistically portrayed as villainous,[58] [59] in great part because the culture is opposed to indulgence in activities like art, music, and dancing (but weirdly pro-sex—more on this in future chapters). This comes from a belief that emotions should be viewed with extreme skepticism (unless said emotions are tied to fervent theological and metaphysical research).

Secular Calvinists typically view emotions as a product of evolution with no inherent value. Humans feel the emotions we do because our ancestors who felt them had more surviving offspring—they are nothing but a scar left by our genetic history. To a secular Calvinist, pursuing positive emotion for its own sake is as feckless as chasing after a fentanyl high. One might even go so far as to say negative emotional states are “better” because they are safer from an addiction/distraction-from-values standpoint. This mindset naturally produces the societal stereotype that Calvinists are obsessed with self-denial, pain, and suffering.

Morays around emotion play such a pivotal role in the Calvinist cultivar that if you look at historical Puritan language, you will find the word “sad” used as an adjective with positive associations, connoting something closer to stern, dignified, and contemplative. Culturally devoted Puritans, for example, would go out of their way to wear what they described as “sad” colors.

The disregard for emotion common in the Calvinist cultivar is not actually tied to the five points of theological Calvinism. Similarly, not all five points of Calvinism are major cultural factors. This exemplifies how religious philosophy alone does not explain 100% of a religion’s associated cultivar. It also explains why the modern theological revival of Calvinism did not revive Calvinist culture more broadly.

This causes Calvinists to see both self-indulgent hedonism and luxury as sinful. Because of this, historically, they had little motivation to spend money on themselves and saw most forms of charity as sinful virtue signaling. As a result, they reinvested almost all their money and time into their companies or specific charities meant to increase the efficiency of other people (such as libraries and schools). This constant self-reinvestment is how Calvinists gained the reputation for inventing modern capitalism[60] [61] and for producing very wealthy but miserly Ebenezer Scrooge-like characters. (For more on this subject see “Calvinist Stereotypes in Media” in the Appendix on page 721.)

For an example of what this ruthless, businesslike culture looks like in practice, here is a text Malcolm received from his mom when she heard about our pronatalist advocacy work:

“What’s your plan to monetize this new interest of yours?

Remember: everything is transactional.”

Calvinists were famous for proselytizing less than other denominations because they believed their world perspective was obvious to anyone who would just put in the mental effort and shed their biases (this stance also led to the culture’s relative extinction). Calvinist groups appeared less like a religious cohort and more like a really intense book club for those obsessed with living the most technically correct life possible and exploring the truth behind our metaphysical reality. This can be seen in stereotypes like:

“Calvinists are “cold,” “heady,” and “condescending.” They think they have it all figured out and everyone else is blind, slow, or stubborn. They’re so lost in their books, they’re not interested in the needs around them.”[62]

While there are reams of Calvinist polemics and theories about better ways to live “correctly,” there is very very little written about what it is functionally like to live within the culture (outside of the more-communally-oriented Puritan branch, which is fairly well-documented due to its foundational role in the American colonies).

Occasionally you will find modern figures who leave Calvinist culture and write about what it was like to be raised within it. A good example would be Aella (a popular sex researcher and friend of the authors), who wrote of her upbringing:

“Conversation with him (her dad) was a daily challenge. He would frequently make blatantly false statements—such as “purple dogs exist”—and force me to disprove him through debate. He would respond to things I said demanding technical accuracy, so that I had to narrow my definitions and my terms to give him the correct response. It was mind-twisting, but it encouraged extreme clarity of thought, critical thinking, and concise use of language. I remember all this beginning around the age of five.”

This type of exercise persisted within my family even after it had secularized and reflects the Calvinist culture’s obsession with imparting a way of thinking and engaging with ideas as much as any specific idea.

The most offensive concept in Calvinist culture is the belief in “elect” individuals—that not everyone is or has the potential to be “saved.” This view is the product of a deterministic perspective on reality. Theologically, this means God knows whether you will be saved or damned before you are born. Secularly, this means some people’s lives do not matter in the grand scheme of the universe.

Whether you matter and manage to become a virtuous, productive person is predetermined. Because of this, you can speculate about your role in the timeline by reading the tea leaves of your heart: Every moment of procrastination or moral failing is a sign you may not stand among the elect. Early Puritan diarists are famous for thinking they’re definitely among the elect one day, then doubting their status among the saved the next; constantly vacillating between hope and doubt.

Perhaps, historically, the most important aspect of Calvinist theology was the belief that truth can only come from self-study: That no matter how well-intentioned a person may be, they risk corrupting the truth with their own perspective and biases if they attempt to guide you to it. This is why at some traditional Calvinist churches, churchgoers would sit and read their own Bibles rather than listen to a sermon-delivering priest.

The Calvinist insistence on finding truth independently produces an ethos of extreme skepticism—if not innate hostility—toward centralized authority at anything above a local level. As Calvinists see it, virtuousness is achieved through every human’s internal struggle with their fallen state. Thus, the more humans become involved in a thing, the more evil it is likely to be (e.g., big governments and companies are seen as more evil than small ones) and nothing is more evil than one human exerting control over another.

Calvinists were fervently pro-independence and anti-slavery, but less out of a belief in equality and more because they saw the removal of agency from another person as the highest order of evil an individual or institution could commit. Famously, John Brown and his family were radical Calvinists and multiple sides of my own family also hunted or otherwise fought against slavers—both by leading the Big Thicket Jayhawkers and by being heavily involved with the founding of the Free State of Jones (15 of the 50 founding members were either siblings or nephews of my direct ancestors).[63]

This belief is reflected in the way we construct this book and The Pragmatist’s Guide to Life. In each, we present an example of how things might be done while insisting that readers independently draw their own conclusions after thinking through matters on their own terms. To us, writing a book that tells someone how to think about the world robs that individual of agency.[64] From our cultural perspective, robbing a person of agency is an act of evil.

So, while Calvinists see striving for equality as silly, their mandate for maximizing individual freedom is absolute and uncompromising to a point of apparent absurdity in other cultures’ eyes. The concept of the elect inherently implies that not all humans are equal, at least when it comes to being “saved.” While some people are born evil, and others are born lazy, it is wrong for anyone but that person to pass judgment on the content of their character.

Calvinist culture is basically dead due to its low post-secularization birth rate. Calvinists’ obsessive research into the metaphysical nature of reality and cultural emphasis on accepting hard truths drove their branch to be one of the first Christian sects to “secularize.” As such, their culture was hit by a collapse in birth rate a few generations earlier than the groups that are getting smacked with it now.

The Calvinist tendency to manifest more as a worldview than a community contributed to the culture’s downfall. As it began to secularize, community-oriented members tried to start unique and separate movements (often some form of deism) or were absorbed into adjacent cultivars (typically the Unitarian Church, Baptist Church, or Pentecostal movement). Only predominantly secular families maintained original Calvinist traditions as they weren’t exposed to any traditions of new Christian sects that might replace them.

Malcolm, whose parents were secular, would not even know his family was Calvinist had he not received a letter from his dead grandfather as part of his will urging him to not stray from “Calvinist values,” which prompted him to look into his family’s history and realize: “Oh, this is why my parents do all those weird things.”

A tendency for Calvinism to be contextualized as “the obvious truth free to anyone who looks hard enough”—and not a distinct culture—is part of why it lacked the sort of cohesive self-identity common among even secular Jews. A cohesive cultural narrative and sense of community identification is why Judaism has secularized fairly successfully while Calvinism largely fractured upon secularization.

We only present this explanation of Calvinism so that our readers can see the lens that distorts our view of reality and replace it with their own. Because our perspective inherently corrupts the information we share, we must be transparent about our biases so you can mentally correct for them. As a family, we can only save our own culture. You must take responsibility for saving yours. If we wrote this book true to form, readers should be able to apply its principles to any theology.

Why is Cultural Diversity Important?

Back on topic we go!

Why are we trying to develop a method for editing cultures that gives them a higher survival rate and distribute that method to as wide a diversity of cultural traditions as possible?

Why are we not just privately fine-tuning our internal family culture and disregarding the rest of the world? Clearly, we adore our own culture given how much we pontificate upon it; why would we intentionally create cultural competition when our culture is designed to produce a fairly large population on its own?

Suppose a group of scientists knew the world’s temperature was going to drop 50 degrees, but they only had time to genetically engineer 50 species of plants to survive in this new environment. Would it be optimal for them to genetically engineer 50 closely-related species? Of course not; these scientists would select for maximum genetic diversity as doing so yields the highest odds that something survives in this new future.

When a culture dies, you lose thousands of years of history and experiences that are unlikely to be recaptured. Someone told us it is offensive to equate South Koreans’ upcoming demographic collapse to genocide, so allow us to clarify that allowing a people to go extinct is whatever differentially makes genocide worse than mass murder.

[The immorality of letting a culture die] = [the immorality of genocide] – [the immorality of murdering an equal number of people].

There is also a selfish reason to promote cultural diversity: Being in a diverse and healthy multi-cultural ecosystem benefits our family’s culture. Every time we see some white nationalist trying to turn the United States into a white Christian ethno-cultivar nation-state, we can only shake our heads at the stupidity of the endeavor. Do they think their treasured “Western Civilization” evolved in homogeneous ecosystems? That Ancient Greece was homogeneous? That Alexander the Great’s forces were homogeneous? That Rome was homogeneous? That Medieval Europe was homogeneous? Why is their culture so weak now that it can only survive in a hermetically sealed pod?

We have heard some seriously argue that all culturally diverse empires die. This is an insane argument, given that all empires that have ever existed have died. Every one of humanity’s most productive, expansive, and culturally dominant civilizations has been diverse—from New Kingdom Egypt to the Roman Empire, Umayyad Caliphate, British Empire, Achaemenid Persian Empire, Maurya Empire, Qing Dynasty, and American Empire (we actually struggle to think of a single great empire that was culturally homogeneous at its height—maybe the Mongol Empire, but if that is the standard bearer for your goal … yikes).

Other nations have successfully become ethno-cultivar nation-states, so we know exactly how it turns out (just look at Korea or Japan). Ethnically and culturally homogenous societies have some of the lowest birth rates of any cultural ecosystem and are wildly fragile. In contrast, not only are some of the highest birth rate post-prosperity cultural ecosystems incredibly diverse (consider Israel), but when people from culturally homogeneous ecosystems move to culturally competitive ecosystems, their birth rates shoot up.[65]

Is it so surprising that a culture unchallenged by competition would become more fragile than one constantly sharpened by it? We explore this topic in the chapter: “Immigration and Conservative Values” on page 592, but in short, if your culture is on life support, putting it in a hermetically sealed room just gives it a chance to die in peace.

Every time we hear one of these white nationalists talk on this issue, we can’t help but visualize a 150-year-old frail corpse of a man with sunken eyes in a sealed pod (basically Mr. House from Fallout New Vegas) feebly pounding his chest, proclaiming in a raspy voice how superior, strong, and virile he is. When someone reaches for the latch on his pod, he begins pathetically hyperventilating and screaming in a panic that he will die if his pod seal is broken.

Building The Index: A Cultural Reactor

One of our goals with this book is to recruit new participants for what we call the Index: A “cultural reactor” that catalogs intentionally constructed family cultures and monitors their outcomes intergenerationally while distributing said information in a way that allows all participating cultures to improve at a faster rate than that of a non-cultivated society. We want to make it possible for cultures in the network to improve faster than normal intergenerational memetic evolutionary powers would allow through a system analogous to horizontal gene transfer in gene therapy or lateral gene transfer in bacteria.

To put it another way, we don’t want anyone to read this book and make the same choices we made. Instead, we want you to either be inspired to identify, reinforce, and restore the positive elements of your own ancestral culture while making them resistant to fertility-lowering memes or experiment with constructing something totally new from an amalgam of different cultural beliefs.

While the Index is an ambitious project that won’t start seeing much purchase for a few generations, it is still worth starting now if we want a shot of preserving at least some at-risk cultures before they go entirely extinct.

We also hope the Index will act as a database of families that can be used to opt-in for traditions that require larger populations than any one house can front (e.g., larger celebrations, dating markets, etc.). This organization is called the Index because its primary goal is to act as a repository of information about the cultures in its wider ecosystem (and not to serve as any active actor on those cultures).

Cultural groups join the Index through the “House” model, in which a House is the atomic cultural unit, a distinct set of traditions and ways of seeing the world. This atomization makes it easier to classify and record cultures while giving them an opportunity to update or redefine themselves intergenerationally.

To give an example of how this works: We, Malcolm and Simone, have created “House Collins,” which is the bundle of traditions we outline (at least in part) in this book. When any of our children prepares to have children of their own, they can choose to either remain in House Collins or create and take ownership of a new set of traditions through the creation of a new House—all while not fully losing their connection to the parent culture, as this new House would still be a member of the Index.

This spares multicultural families from devolving into a watered-down manifestation of each contributing culture. These families won’t feel obligated to forsake one culture entirely or try to raise children in full versions of each contributing culture in a fashion unlikely to inspire their children to pass down both cultures fully to kids of their own.

The Index and House system allow partners in a new family to reflect on the aspects of their birth culture—and other cultures to which they’ve been exposed—that have most significantly improved their lives, then weave them into a single, integrated, new culture in a way that is supported and considered normal by others in the Index network. This stands in stark contrast to many stricter cultures that shun family members who choose to deviate—even slightly—from central doctrine.

Better still, the Index allows distant descendants to review statistics on how families pursuing specific traditions fared, inspiring them to adopt particularly successful traditions from cultures unrelated to their own.

As you read this book, ask yourself:

“How would I construct my own House? What elements of my ancestral and chosen cultures are worth preserving? What elements of my current culture would I totally change? What would make this culture appealing to future generations, and how would the culture be designed to enable future members to iterate and improve upon it?”

Perhaps you’re thinking: “What if I don’t have kids? Can I still join the Index?”

See the Appendix chapter: “On Houses Founded by Sovereign, Childless Individuals” on page 723. The answer is yes, but it is objectively harder to build an intergenerationally improving cultural unit if you don’t have kids.

The Fundamentals of Culture Crafting

A culture’s growth and long-term viability are dependent on only four variables:

- Cultural Adoption: The rate at which new adherents are converted

- Birth Rate: The rate at which members have children

- Cultural Fidelity: The probability someone raised within the culture will stay within it

- Death Rate: The rate at which members die

Before digging into these four variables, let’s explore how they interact.

The Cultural Growth Formula

Relative Cultural Growth Rate =

(Relative Birth Rate – Relative Death Rate) * (Cultural Adoption) * (Cultural Fidelity #0-1)

Cultural Adoption

A culture can grow merely by appealing to and converting outsiders. In practice, cultures with high cultural adoption proliferate over the short term but die quickly over the long run. Why? A common attribute that makes cultures seductive is “easy and forgiving” elements, which in turn contribute to low birth rates.

Strong cultural adoption rates are not as important as one might imagine: Even cultivars with active missionary mandates, like Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses, have high birth rates to thank for the lion’s share of their growth. For the most part, religions almost only grow through conversions over very limited temporal and geographic windows. Even when religions do grow rapidly through conversions, they often fail to spread their original culture, instead forming a new cultivar which is a mix of local culture and the new theology.

This is not to say that cultural adoption cannot serve as a major growth driver for a cultivar. Successful proselytization is commonly achieved through harvesting the children of another culture at a very young age in something we will call the “reverse cuckoo strategy”—because they snatch eggs from others’ nests.

Quakers, for example, grew by specializing in educational fields. Shakers gained adherents by specializing in orphanages. Ultimately, however, both Quakers and Shakers began to collapse when government-backed alternatives wiped out their top recruitment channels.

Other top tactics used throughout history by cultivars to grow rapidly through conversions include (in order of descending efficacy):

- Conversion Incentives: Offering tax-advantaged status or highly sought-after jobs only to members of the culture in question can significantly boost conversions. This method was leveraged by both Roman and Islamic empires to significant effect.

(The current university system uses this strategy to convert people by controlling “elite access” in our society and requiring a college degree at one of a few institutions to enter it, then using said institutions to culturally convert people out of more “traditional” birth cultures.) - Violent/Forced Conversion: Military conquest, followed by intermarriage (in other words, killing the men and marrying the women) and/or state-controlled child-rearing has also been used to boost cultural adherence (as Canada did with some of its native populations through the Canadian Indian residential school system). This type of child conversion is much less effective at wiping out native cultivars than tricking non-members into giving you their kids willingly.

- Missionary Work: By creating a culture-wide expectation that some or all adherents will devote a certain time or amount of their lives to missionary work, as Mormons do, a culture can at least moderately boost cultural adoption rates.*

*While the average Mormon missionary baptizes 2.43[66] people, many of these baptisms are out of convenience (e.g., “You can use our soccer court after you get baptized”)—even though missionaries are technically not supposed to do this.

More than 50%[67] of those baptized on missions leave the church within a year and within a few years, 75% have left (according to BYU and Reuters,[68] at least). If the church baptized 125,930 people[69] in 2021, total membership was 16,663,663, and the average Mormon lives 85 years; this means the average Mormon converts 0.16 people who stay in the church for more than a few years.

This number feels way off. Our guess is the church chose to include in their statistics anyone who had ever been baptized as a member, so we went to a third-party source to get a different data set. If we use that source, which claims there are 4,400,000[70] active Mormons, then the average Mormon converts 0.6 people in their lifetime. While this is not great, it is at least a viable means of spreading if used in addition to above-repopulation-rate birth rates.

We performed this math to demonstrate that even in best-case scenarios (with a cultivar that both aggressively tries to convert people and is largely viewed favorably), missionary work is only marginally effective and seldom capable of conversion at “above repopulation rate” (e.g., >1 convert per member per lifetime) outside of cases in which the culture controls child-rearing institutions (Quakers and Shakers) and cases in which the culture controls the state apparatus (Roman and Islamic empires).

Birth Rate

Birth rate is the most important cultural growth factor. Cultivars with low birth rates are virtual non-players in the game of civilization and can largely be ignored by your culture once you have addressed any bleed they may cause.

For more reading on this topic, dive into “K vs. r Selection in Cultivars’ Birth Rates” on page 724 of the Appendix (or the earlier recommended “Why are Birth Rates Falling” on page 671 of the Appendix).

Cultural Fidelity

Cultural fidelity represents a group’s rate of cultural “bleed:” How many people raised in Culture X stay in Culture X and raise their own kids within it? Fighting cultural attrition is a uniquely difficult challenge in a post-internet age that has compromised many previously effective tactics.

Tactics that worked better pre-internet:

- Threats of shunning: This is only very effective when (1) a culture is geographically isolated, leaving shunned members with no other group to join, (2) a culture is so unique a person will have trouble integrating in wider society (or the culture intentionally prevents a person from acquiring skills that would allow them to integrate into wider society), or (3) a culture provides copious social services on which members rely in everyday life.

- Warnings about not-quite-true consequences: These cultures tell people things like, “You will be punished with a terrible life and no one will ever love you if you leave our culture.” This does not work well any more because threats like this can be easily undermined by a few simple internet searches.

At present, the most effective way to impart cultural fidelity is by creating a culture that fosters pride, strategic advantages, and human flourishing. If people are clearly better off thanks to their culture, they are more likely to raise their children within it and remain loyal adherents themselves. For this reason, the cultures with the highest cultural fidelity are typically either tough to convert into (to ensure a level of quality / exclusivity among members) or require rigorous lifestyle adjustments demanding more willpower than most people have (which naturally weeds out weak-willed applicants).

Granting this level of strategic advantage to a culture requires a certain amount of flexibility. A culture that granted tactical advantages in feudal Japan is different from a culture that grants tactical advantages in Japan’s modern mega cities. If a single culture is to become a throughline between many successive generations, it must be capable of adapting.

Death Rate

When death rates were much higher, a culture’s ability to impart behaviors that reduced odds of death granted it a significant advantage. Consider Islamic ritual purification, Wuḍū, which involves washing one’s face, hands, and feet with clean water (e.g., it is OK to use water from melted snow but not water that may have touched urine or a dead animal). It is hard to argue that, all other things controlled for, a culture that had its adherents washing five times a day would not have a lower death rate than other cultures in a pre-germ-theory era. It’s wild to think that this knowledge was imparted through cultural evolution into a tribe of desert nomads (and later adopted by Islam) centuries before Joseph Lister and Ignaz Semmelweis arrived at this knowledge through science.

Some cultures evolved and adopted practices that helped adherents survive in specific conditions, such as desert environments or hostile frontier landscapes (consider Inuits, who developed a culture enabling them to live in extremely cold environments[71]). Essentially, these cultures evolved traditions that allowed them to thrive within specific environmental or societal niches considered too hostile to other cultures.

Even though death rates are much lower now than they used to be, modern cultures can still secure a competitive advantage by imparting healthy habits to adherents. A culture less likely to be plagued with obesity and addiction will outcompete an otherwise identical culture that lacks these defenses.

Types of Cultures

Cultures can be roughly divided into two categories: Contextual Cultures and Cultivars.

- Contextual Cultures (e.g., sports team fanbases, clubs, local drinking cultures, etc.) only appear in a specific contextual framework.

- Cultivars are the lenses that color an individual’s view of reality. This is the type of culture most of the book is focused on investigating.

Cultivars themselves can be thought of as belonging to one (or more) of a few broad groups that warrant some exploration before we proceed.

Hard Cultures

Hard cultures are almost always centered around young religious traditions. (When we say young, we do not mean the branch religion is young but the way it is being practiced now is—e.g., Jehovah’s Witnesses are part of a century-old religious tradition but are practicing things differently enough to be functionally young.)

In addition, hard cultures often feature a few characteristics that prevent bleed:

- They often encourage adherents to wear unique outfits or perform rituals that cause them to feel like outsiders when mixing with other cultural groups.

- They attempt to prevent adherents from associating with other cultures to the extent that they may even shun them for doing so.

- They almost always provide copious social safety nets for members.

- They incentivize members to proselytize (either to convert people or reinforce personal narratives about how great it is to be a member of that in group) in a way that would produce significant cognitive dissonance if they ever decided to detract from the culture (though this proselytization is rarely effective at increasing cultural spread in any significant fashion).

In addition, hard cultures typically promote an internal locus of control, encouraging adherents to take personal responsibility for their failings in life.

Examples of Hard Cultures

- Mormons

- Jehovah’s Witnesses

- Scientologists

- International Society for Krishna Consciousness members (known more commonly as followers of Hare Krishna)

- Haredi Jews

- Evangelical Protestants

- Amish

Characteristics of Hard Cultures

Until recently, hard cultures represented some of the world’s most successful civilizations, having a low bleed and high birth rate (which led them to grow at a higher rate than other cultures, making them inevitable beneficiaries of our society). In response to recent society-wide changes, this edge has eroded. In the last decade or so, many of these cultures’ attrition rates have skyrocketed while their birth rates have begun plummeting.

Consider Mormons: Their cultural bleed rate is currently 36% per generation (above that of even Evangelical Protestants) and as of this book’s initial publication, the Mormon population in Utah has almost fallen below replacement rate (2.1), a significant drop from the 3.14 birth rate enjoyed by the community around a decade ago (the USA’s highest birth rate at the time). What was one of the world’s fastest-growing cultures is, by the data, about to experience a catastrophic crash. This problem is anything but constrained to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.